On June 20, 1975, two cinematic movements were born on the fins of one mighty fish.

The latter was, of course, a great white shark, and the first movement was the invention of the blockbuster. Some might argue that happened three years earlier with The Godfather, but the majority opinion still holds for Jaws. And if Spielberg’s marine thriller loosened the hinges, George Lucas blew the doors off two years later with Star Wars.

It’s a legendary start to a fascinating story, but one that has already been skillfully told elsewhere. Look no further than Tom Shone’s excellent book Blockbuster to witness the first three decades of big-budget movie making.

Yet, what of that second movement? It refers to a shift less bombastic than the first, but just as resounding in its cultural impact. To trace its roots, however, we must go further back in time, to November 22, 1963.

It has been said that JFK’s assassination, and the Warren Commission’s subsequent — and eventually mistrusted — report, marked the beginning of when Americans stopped implicitly trusting their government. The de facto start of the Vietnam War less than two years later hardly sweetened the national mood. Nor did the year 1968, which alone saw, among other tragedies, the murders of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. Then came Watergate, in 1972, to cap it all off.

These being just the highlights, one might excuse the average citizen for considering this period a downer of a decade.

Yet, out of immense pressure are formed sparkling diamonds. To wit, the period from 1967-1974 has come to be seen as something of a second Golden Age for Hollywood. And with good reason. This volatile stretch gave us Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the first two Godfathers and Chinatown, just to name a few.

Much like the music of this era, the movies could hardly be accused of playing it shallow. Beyond the Oscar lights and din of critical praise, however, followed one inevitable consequence: not too many people were walking out of the theater with a smile on their face.

They didn’t with Jaws, either. But then, they wouldn’t. That’s not how hope begins. Before you can look up, you have to look forward. Johnny Cash¹ and Neil Diamond² each sang about this phenomenon; Winston Churchill immortalized it with the words, “If you’re going through hell, keep going.”

What does any of this have to do with a man-eating shark? Jaws may have been a horror movie, but it scared its audience differently than predecessors like The Exorcist or Night of the Living Dead. For the first time, there was no time to wallow in the darkness. Unlike its main character, the movie itself didn’t drag you down.

After a showing of Jaws, you were more likely to catch your breath than hang your head. For in the film’s terror, there was also an exhilaration that hadn’t existed before. Shone highlights this sentiment while relaying the movie’s communal pull:

The Godfather…was essentially a study in collective isolation; you watched it alone, no matter how full the cinema was, and you left the theater eying your fellow moviegoers with new unease, uncertain whether you would care to share a theater with them again. But Jaws united its audience in common cause — a shared unwillingness to be served up as lunch — and you came out delivering high-fives to the three hundred or so new best friends you’d just narrowly avoided death with. And then you came back the next day to narrowly avoid it again…you watched Jaws again for the same reason that people head back into a thrill ride, or keep doing bungee jumps.³

Clearly, a corner had been turned. But the destination was still a mystery.

A major clue was unveiled on Oscar night, 1977. In one corner sat the Best Picture favorite, All the President’s Men. Besides being an excellent film, it perfectly encapsulated — this time in literal form — the Watergate-fueled paranoia that prior conspiracy thrillers like The Parallax View and The Conversation merely mirrored. As much as any other movie, All the President’s Men was a celluloid emblem of the past decade.

Then there was the other corner, which held something completely different — and new. An underdog if there ever was one, it wore its blue-collar Philly roots like a badge of honor. And wouldn’t you know it, Rocky won.

Was Stallone’s plucky fairy tale a better film than All the President’s Men? Not likely. But then, the Academy Awards are just as often a popularity contest as they are a defining arbiter of cinematic excellence. And, like America itself, Rocky Balboa had recently taken his fair share of lumps. Yet he emerged—not just alive, but victorious.

A few months later this trend of cautious hope would go intergalactic. Star Wars wasn’t the first feel-good box office smash, but once again, things felt a bit different this time. It was the first blockbuster to so seamlessly combine action and comedy. Forget special effects — the tone of this movie hardly existed before 1977. Sarcasm and adventure weren’t supposed to share the screen in such quantities.

Like a locomotive leaving the station, it took a while for the trend to gain speed. The likes of Smokey and the Bandit and Superman helped, and by the time The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark were setting records, the rest of Hollywood had caught on. Soon it was E.T. and Tootsie filling theaters, and the trend was no longer such; it had become the norm.

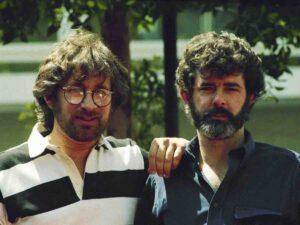

Largely on their own, and surely without intention, Spielberg and Lucas had injected their industry with an infectious energy, a bright wonder that permeated and dispelled the thick cloud hanging low over the previous decade.

Nevertheless, they had help, perhaps from one of the most unlikely sources. For Hollywood had not cornered the market on confidence. The surrounding culture had also found its smile, thanks to a leader who just happened to know a thing or two about the movies.

Ask any number of people to name an ‘eighties movie,’ and many will immediately turn to John Hughes. Indeed, the coming-of-age maestro had a near-monopoly on high-school dramedies throughout the decade. Hidden beneath their sheen of zeitgeist-shaping popularity, however, is the likelihood that they wouldn’t have worked at any other time.

Once the nineties rolled around, irreverent, sometimes jaded teen comedies such as Clueless and Mallrats were setting and reflecting the cultural tone. The Brat Pack would’ve come off as, like, total squares. And before? Well…just consider The Graduate.

When Dustin Hoffman rescues Katharine Ross from the altar and they make their public-transit getaway, the movie’s tone quickly shifts from happy to heavy. The couple’s faces fall before Simon & Garfunkel even have time to mention the sound of silence. And all at once, we see it in their eyes: a grand aimlessness. They don’t know what they want, nor where to find it.

This simply wouldn’t fly in Hughes country. It’s not that his characters don’t deal with growing pains and crises of identity — it’s that they always seem to emerge from them. Some cross the finish line with their goal in hand, others merely glimpse their destination. But the view is always clear. And if not for them, then the movie itself. For theirs is a sharply defined world in which good and bad are as black and white. It is a world of assurance.

None of this is, of course, about John Hughes. It all actually leads back to Ronald Reagan.

Love him or hate him, as president he left his mark on the culture of the decade more than anyone. Reagan was the eighties. And Hollywood was no exception.

During Reagan’s administration, America experienced staggering military and economic growth. As a whole, the nation was finally able to shed the shame of Vietnam and, at least in its own consciousness, embrace the side of virtue in the Cold War. More than most heads of state, Reagan understood the role, and power, of being a cheerleader for his country. His entire presidential legacy could arguably be summed up in two words: “can do.”

And yes, this flows all the way down to Sixteen Candles and Pretty in Pink. But perhaps more illustrative examples lie at the heart of the decade, and could truly be called the triumvirate of ‘eighties movies.’

The first two are Beverly Hills Cop and Back to the Future, which deserve mention for similar reasons. Each was a massive hit brimming with an exuberant ingenuity that seemed to etch in stone the optimism that Spielberg and Lucas had originally discovered. If, back in 1985, you managed to escape the theater without tapping your toes to Stir it Up or The Power of Love, you were surely in the minority.

The third example is Top Gun, in which Tom Cruise’s million-dollar smile shares top billing with America’s own hypersonic patriotism. To be sure, this movie became one of the navy’s best recruiting tools. But it also stood as a symbol of the country’s collective attitude. Nothing demonstrates this fact better than a slightly different movie, released six months earlier.

Iron Eagle was always going to be a poor man’s Top Gun. But their tone could hardly have been more similar and their inspiration came from the same place. The former simply had the decency to state it bluntly. Case in point: early in Iron Eagle, amateur fighter pilot Doug Masters (Jason Gedrick) is doubting the American military’s ability to rescue his father, an Air Force colonel whose plane has just been shot down in North Africa. Doug mentions it could be a debacle along the lines of the Iranian hostage crisis a few years earlier. But his friend Reggie sets him straight:

Oh, no, that was different. Mr. Peanut was in charge back then. Now we got this guy in the oval office who don’t take s–t from no gimpy little countries. Why you think they call him Ronnie Ray-Gun?⁴

These lines are delivered, and received, with straight faces. No telling smirk, no cheeky skepticism. Not for over twenty years — nor anytime since — had the popular culture put such faith in its government. Whether this was a net positive or negative lay in the eye of the beholder.

In the end, it all boils down to belief. That’s what the eighties were really about. Belief that right and wrong did exist, that the difference between them wasn’t that complicated, and that there was room enough for everyone on the same team, whether you were a Goonie or a grandpa.

This conservative conviction was, ironically, born from liberal minds. Spielberg and Lucas represented a west coast worldview whose political distance from the Reagan White House mirrored its geographical separation. To say the least, they likely would’ve been nonplussed with how seamlessly their creativity complemented Rawhide’s confidence.

And yet, many would say this accidental bipartisanship led America out of a darker world and into a better one. At least on the silver screen.

¹ Get Rhythm

² Song Sung Blue

³ Shone, Blockbuster p. 37

⁴ Kevin Elders and Sidney J. Furie (screenplay), Iron Eagle, 1986