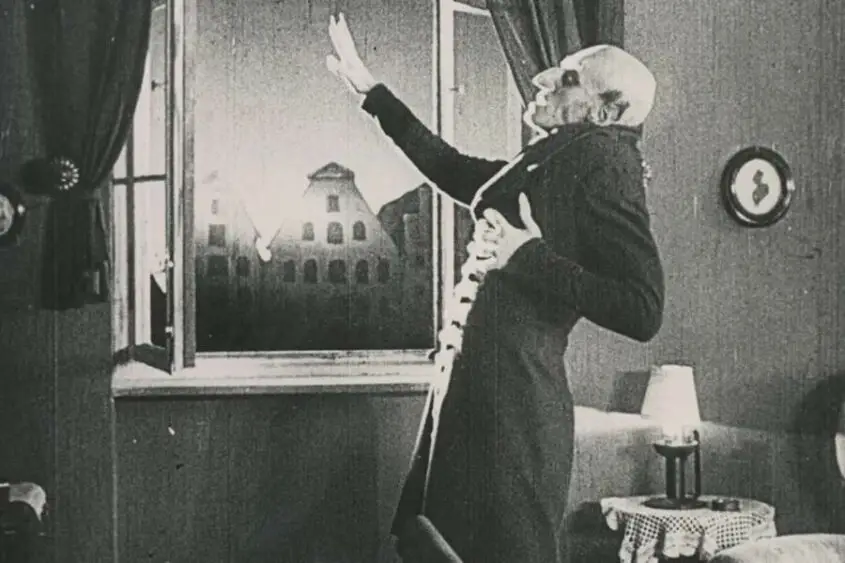

Back in 1922, in the era of black and white and silent film, there lurked a movie about a vampire. And this vampire was beastly. It had an awkward caved-in posture, bat-ears, claw-like nails, and rodent-like teeth. Called Nosferatu in the film of the same name, and played by German actor Max Schreck, this vampire was not at all like the gorgeous, sophisticated vampires that actors Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt embodied in the mega-hit Interview with the Vampire (1994). Nor was this vampire like the young, sweetly romantic vampire that Robert Pattinson portrayed in another blood-sucking mega-hit Twilight (2008). No, this vampire was different. And he was positively terrifying.

An excellent example of “Gothic horror” cinema, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror is a beautiful symphony, masterfully blending both artistic genres of “Gothic” and “horror.” “Gothic,” which is a reference derived from ancient Germanic tribes and used to describe certain cultural foundations such as literature, architecture and so on, can unsurprisingly be enjoyed throughout this German film. Gothic highlights the shadowy, murky, and mysterious that peeks at us around every dark, high-ceilinged corner. Or, it’s behind every razor-sharp, pointy-designed doorway. What hides on the other side? Gothic asks these questions.

Now merge that macabre, downright moody architectural backdrop with the artistic genre of “horror,” and the result is a match made in heaven. Or, in this case, hell. The towering Gothic castles of Nosferatu, with secret passageways and winding corridors filled with mists of a bygone entity, all evoke a deep, instinctive fear. This atmosphere sets the stage so that when gruesome, dangerous things start happening, terror can take hold. Gothic gives horror the ability to really soar. Or again, in this case, successfully puncture and slice.

Nosferatu is #2 on our list of the scariest horror films ever made. Watch the full list below (Duration: 3:14 minutes):

Directed by F.W. Murnau, and based on a screenplay by Henrik Galeen, Nosferatu tells the tale of a simple German real estate agent, Thomas Hutter, who is sent to the mountains to broker a real estate deal with his boss’s new client. This client is named Count Orlok. Once there, and after enduring a bit of foreboding and dread due to his strange, unsettling journey there, he is met by more oddities. Enter a bloody finger, and neck-punctures that Hutter tries to emotionally brush off as mosquito bites. Could his castle-host really be a bad man who is trying to injure him?

All told, Hutter manages to escape the castle and return home. However, what happens next is worse. Count Orlok, who has purchased the house in Hutter’s German town (via the aforementioned real estate deal), enters his new hometown and proceeds to commit one blood-sucking murder after another.

Like the death count, denials in the town mount. Blame for the murders falls on a mysterious “plague,” until Hutter’s wife, Ellen, digs deeper. (Sidenote, she’s also being romantically coveted by the dangerous Count Orlok.) Suspecting a more sinister, murderous reason for the deaths, Ellen eventually sets her sights on killing Count Orlok and stopping his vampire reign of terror. The question is – “Will she be able to do it, without being killed by the vampire beast?”

Nosferatu is a flawless piece of artistic imagination that shines with extreme fervor. A piece of moviedom lore – it’s actually an illegal motion picture adaptation of Bram Stroker’s novel Dracula written in 1897. Additionally noteworthy, because The Stroker estate had refused permission for the on-screen recreation of the famous novel, certain things were changed for the movie. For instance, “Count Dracula” became “Count Orlok,” and the word “vampire” got replaced by the word “Nosferatu.”

Later, Stroker’s heirs sued the creators of the cinematic adaptation and ordered that all copies of the film be burned. Call it akin to a witch hunt. However, it was one that ended inconsequentially. It was all in vain. A few copies of the demonic work still existed and were in circulation. The cinematic significance of Nosferatu is immense, and it’s certainly re-entered the cultural zeitgeist this past year with the release of director Robert Eggers’ 2024 Nosferatu.

Considered a horror masterpiece and an important milestone in the road of global cinema, 1922’s Nosferatu is the movie that popularized the mythology of vampires in a way that is still gripping audiences. Though it’s not the first film about vampires (1921’s Dracula’s Death holds that honor), it’s certainly been the most impactful.

So many things that are considered a “staple” in vampire mythology can be traced back to their invention in this film. For instance, Nosferatu instilled the notion that a vampire will die if exposed to sunlight. To establish this well-known piece of vampiric mythology is no small feat. Thank you, Nosferatu.

As for the actor in the titular role, Max Schreck garnered quite a reputation for his memorable portrayal. Critics and audiences applauded, quite literally, his total physical embodiment of the grotesque vampire Count Orlok. This applause grew to such a fever pitch that, back in the day, rumors started to swirl that Schreck was actually a vampire in real-life. Shivers. This proved lucrative for the German movie industry, as people would go to the theatre and watch the movie under the pretense that they’d get to see a “real” vampire on-screen. Max Schreck’s fearsome Count Orlok is still one of the most iconic villains in existence.

Aside from skillfully merging “Gothic” and “horror” to achieve a movie masterpiece, Nosferatu is also, importantly, visually well-made. It has innovative and intelligent use of special effects. Stop-motion photography was the director’s closest friend in this ordeal. In one scene, Count Orlok’s coffin closes by itself after the lid levitates off the ground. A primitive form of stop-motion animation made this possible. A sequence of still images, in which the lid moves closer and closer to its final resting spot, was rapidly shown. With this, director Murnau was able to trick the viewer into thinking that the inanimate object was flying around under its own power.

The same technique is used in the scene where Count Orlok employs his magic to open the hatch of a ship, further amplifying the eerie atmosphere that has already been so meticulously built throughout the film.

Additionally, the German cities contrast well with the Slovakian mountain castles. These towering castle beauties exuberate might and dread, as they engulf the viewers within their occultic charms.

The use of different color filters also affords this black and white film a more mysterious, intriguing quality. The changing times of day and night have been reflected through murky tints of blue and red. This juxtaposition of two highly contrasting colors leads to an almost poetic depiction of the city haunted by a vampire. The use of negative photography to display white trees as the foreground of a black sky is a truly haunting image. The shadows lurk outside our frame of reference. The fear of the unknown elevates tension within our minds.

Back to the performance of Max Schreck and others, some modern reviewers have criticized Nosferatu, calling the depictions “over-dramatized.” But, for the early 1920s “silent film” timeframe in which this film was made, over-dramatization was the norm. After all, most actors were “stage” actors who had recently made the transition from theatre to moving picture. Because of this, where words could not be used to convey emotions in a silent film, it was the body that had to stand in for it. Nosferatu showcases this type of uber-dramatic acting style.

Important, too, Nosferatu’s Count Orlok was a perfect character to be portrayed with over-the-top drama. It fit his whole countenance (pun intended). Anything other than an exaggerated acting style would likely not have done justice to his fright factor. Count Orlok’s odd, scary appearance, mixed with Schreck’s ability to reproduce human emotions on this very scary face (a face that clearly belongs to a monster), is commendable. It gives Count Orlok an intriguing depth; his hypnotic eyes evoke sympathy, revealing a quiet pain behind the monstrosity.

Does Count Orlok like being a blood-sucking murderer? This silent internal suffering reaches the audience without the use of words, and without being explicitly mentioned. Ultimately, Schreck portrays a being that laments his dreaded curse. He’s not the flamboyant vampire character that many vampires are today. Where is Tom Cruise’s velvety, lace-attired Lestat in the previously mentioned Interview with the Vampire (1994)?

Now full disclosure, some of the symbolic elements in Nosferatu stray away from the novel. However, they are smartly used by Murnau in order to depart from the film’s heavily aesthetic tone. Call them welcome balancing factors. For instance, there’s a scientist who gives a lecture on the Venus flytrap (the “vampire” of the horticultural kingdom), and a spider who devours its prey. This all adds to the vampire’s resemblance to predators of the wild.

The question is: “If nature can produce such vampires, why can a human not be a vampire, too?” It’s a very deep question, and one that was completely unexpected to be asked in a 1920s film. Such philosophical deliberations were unprecedented for the era.

Nosferatu, even as an independent movie, is a great one. Even if the questionable factors about the original story are removed, its status as a landmark movie is solid. The film brilliantly portrays the horrors of the beast in the form of a man. The popular image and internal psychology of the vampire are explored with a lot of maturity. We get a story of Dracula at its purest, without any cliches or caricatures. Even better, audiences are left feeling that perhaps even the cast and crew themselves believe in the myth of the vampire, or that its lead character is himself an actual vampire. The film is that convincing.

But another big question remains: “Is Nosferatu scary by today’s standards?” For some, the answer is “yes.” And it’s not just scary, it’s haunting. It doesn’t utilize the cheap thrill of the jump-scare. Instead, and on the flip side, it utilizes skillful manipulation to coax the audience’s emotions through artistry and ideas, atmosphere and images. It doesn’t tell us that vampires can just jump out of the shadows. Instead, the movie shows us that evil can grow anywhere, and unhinged evil always leads to death (both symbolic and physical).

Nosferatu is a poetic, dreamlike black and white silent film (though it does boast haunting organ music!) that allows its constraints to be its strongest assets. Evil needs no voice to haunt us. Nor does it require much color. It shows us that darkness lurks around us all, in the corners of life, just as it lies in the corners of the movie frame. The sunlight often keeps it away. But, once we experience that unrelenting dread that the darkness carries around on its back, we know that we’re in for it.

It’s impossible to dig out from the quiet claws that Nosferatu has sunk into your heart, and the teeth that have bitten into your neck. Puncture and slice. Is that the plague, or something else? Oh no.

Rating: 4/5

Where to Watch: YouTube (free)

For horror enthusiasts, here are our picks for the 10 best Japanese horror films of all time (Duration: 8 minutes)